By Steve Rogers. The article’s author is the Chief of Staff to Zuora’s CEO and was previously an equity research associate. The majority of his equity research experience was on Citigroup’s software team.

Summary

Broad market dynamics are supportive of higher software company valuations due to the increasing demand for their solutions and their decreasing supply as standalone businesses. We believe this is a key indicator that established companies must act immediately to address any deficiencies in their digital and subscription strategies as rising valuations are indicative of the rising importance of digital competencies.

So, what is your company doing to navigate the shift to this new world and are you sure that will be enough to ensure you’re the disruptor, not the disrupted?

Context

In our second installment of this newsletter, Zuora’s CIO, Alvina Antar, will layout her “M&A Playbook” which she created and implemented during her time at Dell in order to standardize the integration process of the many acquisitions the company made. In this piece, we are going to set the stage by laying out the high-level dynamics that have caused established companies like Dell to be uniquely focused on developing digital competencies, often through acquisitions of innovative, small private tech companies.

In the mid-2000s, the simultaneous rise of mobile, social and software as a service fundamentally changed the relationship between businesses and their customers. It was these enabling, self-reinforcing trends that caused customers to demand companies market to them by presenting the right product at the right time through the right channel. Moreover, after the sale occurred, customers required businesses to deliver experiences (not product ownership) which necessitates cultivating long-term relationships (versus a one-time sales). The only way for businesses to meet these expectations was through applications and subscriptions, and thus began the shift to the Subscription Economy that is now ubiquitous.

While the dynamic at the front-end between businesses and customers was disrupted, there was a concurrent disruption necessitated in businesses’ back offices due to the fact that legacy IT environments could not enable a basic subscription business model. The new model of ongoing customer relationships brought to light new metrics to track: customer acquisition costs, price optimizations, upsells and downsells, and customer lifetime value. However, existing business systems failed to provide any visibility into these crucial variables as they were architected for a fundamentally different business and financial model. So, companies began confronting this reality by investing organically (re-tooling internal IT systems, processes and employees) and inorganically (M&A) to develop the digital competencies necessary to survive in this new world.

Meanwhile, public companies since the financial crisis have enjoyed a near 10-year period of reasonably consistent earnings growth due in large part to inordinately stimulative monetary and to a lesser degree supportive fiscal policy. This relatively stable period of cash generation came with one caveat in that significant portions of that cash was concentrated overseas and thus could not be repatriated to be invested domestically. To combat this (while also being heavily incentivized to do so by historically low interest rates), companies borrowed against that overseas cash to invest at the scale they desired (operating/capital expenditures, share buybacks/dividends and/or M&A). This led to companies taking on incrementally more debt over time as M&A and buybacks/dividends jumped to historically high levels.

So, it is through this lense that it is most helpful to contextualize the decisions companies are making and means through which those companies are executing those decisions in today’s world. But, there is an important piece missing from this conceptual mosaic. Because a radically different set of competencies is required to thrive in this new world, it is the innovative technology start-ups that should be taking center stage in this narrative. Below, we analyze trends in the software IPO and M&A markets to finish painting that full picture.

Analysis

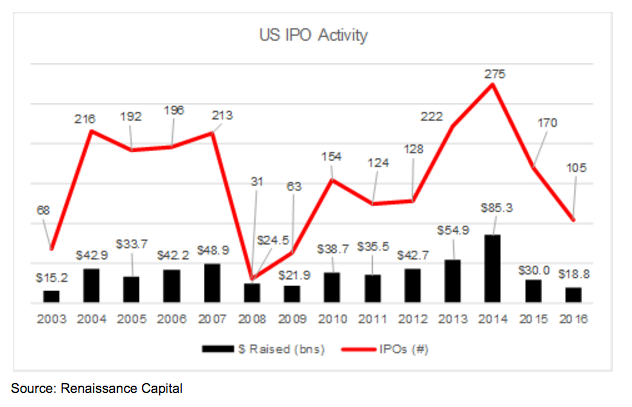

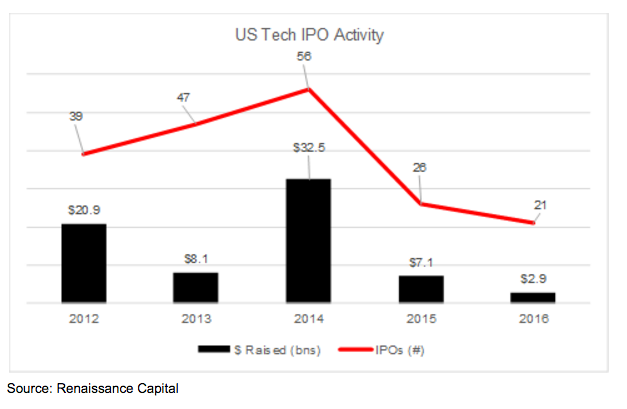

Looking first at the high-level data over the last few years, it’s clear that the 2015-2016 calendar years saw decreased aggregate US IPO activity (both dollars raised and number of IPOs). Unsurprisingly, US tech IPOs follow the same downward trend as total US IPOs.

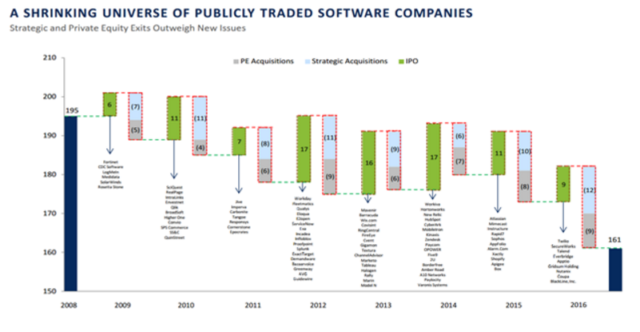

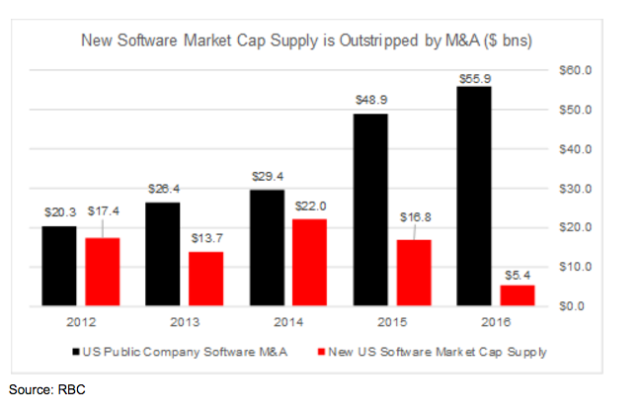

What makes this phenomenon particularly interesting is that while at the same time that US tech and software IPO activity has declined, there has been a consistent pace of software acquisitions. These two trends together have caused the universe of public software companies to shrink meaningfully over the past decade from nearly 200 in 2008 to about 160 today. Looked at from another angle, the value of public US software M&A from 2012-2016 was ~$180bn while the new market cap that came onto the public market over that period was ~$75bn, a nearly 2.5:1 ratio. In 2016 alone, that ratio was >10:1.

Source: GCA Global

Before delving into the implications of this tightening of public software equity supply, it’s worth understanding some of the contributing factors as to why tech and software IPO activity has declined. First, in February 2016, LinkedIn and Tableau both reported results well below investor expectations. Both stocks dropped ~50% the next day causing a broader sell-off across technology and software stocks.

Interestingly, before this market correction occurred, valuations were mainly correlated to growth. Meaning, investors demanded software companies grew revenue as fast as possible with little regard to how efficiently that growth was achieved (ie – how much companies had to spend to grow). But, after the correction, investors demanded a balance between growth and efficiency. This required companies, both public and private, to adjust to those new expectations and re-engineer their business plans to provide the balanced, efficient growth investors wanted. So, this period of adjustment and depressed public equity market valuations caused, in part, the slowdown in US tech IPO activity over the past year.

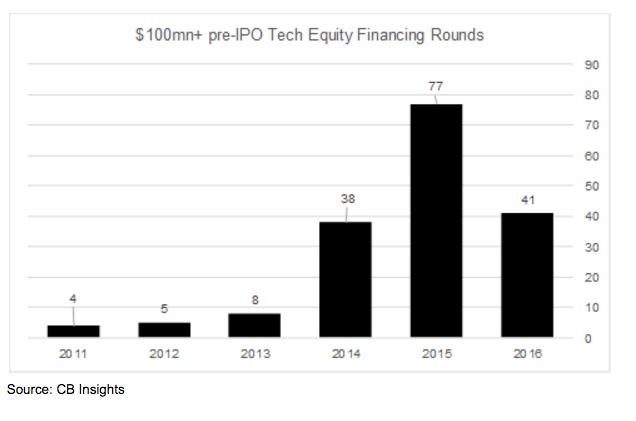

A second reason for the tightening of public software equity supply is the ability for pre-IPO tech companies to raise $100mn+ in pre-IPO financing rounds. Historically, IPOs were the only arena where private companies could raise such significant funding. But, several high-level market dynamics have caused an unprecedented spike in large ($100mn+) pre-IPO financing rounds including: 1) The incremental ease which the rise of social, mobile and software as a service (particularly the availability of IaaS, PaaS) allows startups to scale and scale increasingly quickly, 2) A more mature, competitive private funding market (incubators, VCs and growth equity firms), 3) Historical public market institutional investors (mutual and hedge funds) being more active participants in private market financing and 4) A willingness to take advantage of the historically cheap cost of debt financing. The net result of these trends is private companies seeing the benefits of going public (access to significant funding and the ancillary benefit of those large funding rounds to allow some early investors to cash out) being provided in the private markets, while the costs of going public remaining high.

A third reason for lower IPO activity relates to regulation. Notably, the Sarbanes Oxley Act (2002), raised the cost of going public by requiring more stringent internal controls and disclosures from companies, particularly public companies. At the same time, the JOBS Act (2012) lowered private companies requirements for when they have to register with the SEC in addition to making it easier for private companies to raise money. So, in tandem, these two acts incentivize companies to stay private.

A final reason for the tech IPO slowdown is the macro-economic uncertainty caused by political events like Brexit and the 2016 US presidential election. While the impact of these is tough to quantify, they surely had an impact on companies’ willingness to IPO.

Implications

Given the overarching dynamics outlined in today’s markets, there are a few implications:

1.Given the fact that established companies are rapidly trying to acquire digital competencies to make this shift to the Subscription Economy, demand for earlier stage tech and software companies’ solutions should only continue to increase. This puts upward pressure on valuations, all else equal.

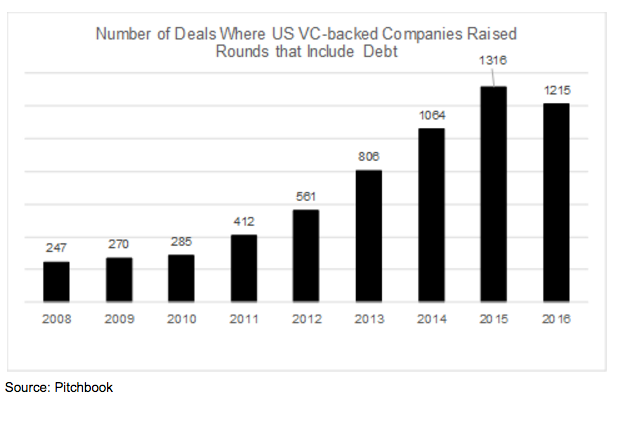

2.Given historically low interest rates (which incentivizes raising debt) and companies’ willingness to raise debt to fund investment, valuations should see incremental upwards pressure beyond the dynamic outlined in implication #1.

3.The shrinking supply of standalone public software companies, all else equal, should continue to create upwards pressure on valuations.

Taking implications #1-3 together, broad market dynamics are supportive of higher software company valuations due to the increasing demand for their solutions and their decreasing supply as standalone businesses. We believe this is a key indicator that established companies must act immediately to address any deficiencies in their digital and subscription strategies as rising valuations are indicative of the rising importance of digital competencies.

We note that some established companies are taking this seriously and acting accordingly. Recent anecdotal examples here are many and range from Cisco paying $3.7bn for AppDynamics (double the initial IPO valuation range), Intel buying Mobileye for $15bn, GM creating a subscription plan for its Cadillacs, Unilever buying Dollar Shave Club for $1bn, PTC announcing a shift to subscription pricing (enabled by re-tooling its internal IT architecture), WalMart buying Jet.com for $3.3bn, etc.

While we could list dozens of other examples, our point here is less about proving something that is already obvious but raising the all-important questions: what is your company doing to navigate the shift to this new world and are you sure that will be enough to ensure you’re the disruptor, not the disrupted?